Chordoma: A Rare Bone Cancer of the Skull Base and Spine

by Mahyar Pakizegee

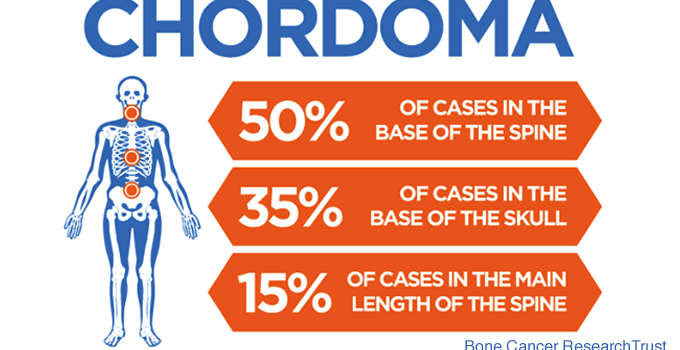

Chordomas are low-grade cancers that can occur anywhere along the spine and skull base. They are thought to arise from the notochord, which is a vestigial structure important in spinal column development. These tumors are quite rare, affecting approximately 1/1,000,000 individuals annually. Of all the cancerous tumors originating from the bone, they account for less than 4%. Chordomas typically present between 40 to 70 years of age, and favor men over women. These tumors rarely metastasize to the body but are locally invasive and aggressive.

Approximately one third of patients have chordomas originating at their skull base. Headaches, double vision, abnormal eye movements, difficulty swallowing and urinary incontinence are common symptoms for skull base chordomas. Though attempting to remove spinal chordomas as one piece (en bloc resection) is the accepted approach, most skull base chordomas fail to be removed by this method. Thus, treatment of these tumors includes minimally invasive surgical resection, as well as radiation therapy. This combination leads to remission for many patients, but some still require further treatment. The goals of treatment include tumor control and maintenance of quality of life.

Pacific Neuroscience Institute in Santa Monica and Torrance, California, neurosurgeons Daniel Kelly, MD and Garni Barkhoudarian, MD, are renowned experts in the minimally invasive surgical removal and treatment of chordomas.

Pathogenesis

Although the underlying causes of chordoma are less understood, chordomas originate in the bone, and as they grow, they destroy the bone and extend to the brain and soft tissue. The primary site of origin is the clivus (hence, “clival chordomas”), which is a junction between two skull bones, the sphenoid and occipital bones. Many tumors breach the dura mater – the covering of the brain and spinal cord – and can cause direct pressure on the brainstem and cranial nerves. Similarly, the tumors can grow into the nasal sinuses, causing blockages which can lead to sinusitis, infections, bleeding or eustachian tube dysfunction.

Symptoms

The clinical manifestations of chordomas differ based on tumor location and size. The most common symptoms of skull base chordomas include headaches (resembling sinus headaches), sinus infections, nosebleeds (epistaxis), and hearing difficulties due to eustachian tube blockage or dysfunction. If the tumor enters into the central nervous system (CNS), it can cause symptoms of brainstem compression and nerve dysfunction. The most common nerve affected is the abducens nerve which controls eye movement, resulting in double vision (diplopia). Other nerves which may be involved include the trigeminal nerve (facial sensation), the facial nerve (facial muscle movement), the vestibulocochlear nerve (hearing and balance), the optic nerves (vision loss), and the hypoglossal nerve (tongue movement). In cases of severe brainstem compression, patients can develop difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), hoarse voice (vocal cord dysfunction), weakness in the arms or legs, and balance or coordination difficulties.

The pituitary gland is situated at the top part of the clivus and can sometimes be compressed or displaced by the tumor. The pituitary gland is the master gland of the body and controls other endocrine glands such as the adrenal and thyroid glands. Hence, pituitary dysfunction can result in symptoms of hypothyroidism or hypocortisolism with symptoms such as fatigue, weight gain, loss of menstrual cycle and impotence / infertility.

Some patients undergo cranial imaging for unrelated symptoms such as head trauma and a lesion in the clivus may be identified. These tumors can be asymptomatic and would not have otherwise been detected. They deserve a thorough work-up and potential treatment given the chance of tumor growth and the development of new symptoms.

Diagnosis

Chordomas are initially diagnosed by cranial imaging, most commonly, computed tomography (CT) scan, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Often, patients have sinonasal symptoms and undergo a head CT by their ENT (ear, nose, throat) surgeon which would prompt further investigation. The gold standard of imaging is an MRI with IV contrast which uses gadolinium, with thin cuts in the region of the clivus, often called a “pituitary protocol”.

If the imaging demonstrates the tumor is compressing the pituitary gland or optic chiasm, further testing may be necessary including an endocrinology and/or ophthalmology evaluation. Pituitary hormones should be assessed and may require more thorough evaluation. A visual field test and optical coherence tomography (OCT) should be considered to measure the extent of vision loss and permanent optic nerve damage.

Given that there are numerous types of tumors that can occur in this region with widely varying treatment options, an initial biopsy is almost always required to establish a pathological diagnosis. This is often performed by the ENT surgeon during an office or outpatient procedure. The pathological diagnosis of chordoma is usually unambiguous and is necessary to guide the definitive treatment of the patient.

Treatment of Chordomas at PNI

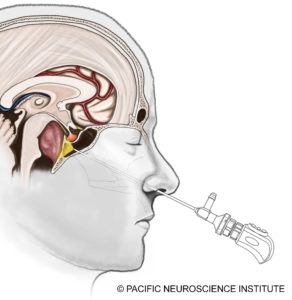

At Pacific Neuroscience Institute and other top centers, the gold standard for chordoma treatment is surgical resection of the tumor. Most skull base chordomas are midline structures and are best approached through a minimally invasive approach such as an endoscopic endonasal transclival approach through the nostrils. Some tumors have lateral invasion such as into the inner ear region, and may require a retrosigmoid craniotomy approaching the tumor from behind the ear in combination or on its own. The goal of surgery is maximal safe resection of the tumor. One should not aim for complete tumor resection if vital functions are jeopardized.

At Pacific Neuroscience Institute and other top centers, the gold standard for chordoma treatment is surgical resection of the tumor. Most skull base chordomas are midline structures and are best approached through a minimally invasive approach such as an endoscopic endonasal transclival approach through the nostrils. Some tumors have lateral invasion such as into the inner ear region, and may require a retrosigmoid craniotomy approaching the tumor from behind the ear in combination or on its own. The goal of surgery is maximal safe resection of the tumor. One should not aim for complete tumor resection if vital functions are jeopardized.

The endonasal operation through the nose is now the mainstay of surgical options and has become increasingly safer over the last 10 years. With the use of surgical navigation software i.e. “GPS” for surgery, Doppler ultrasound monitoring, and cranial nerve monitoring, the risks of vessel injury including bleeding or stroke, and nerve injury have decreased. Additionally, the advent of a “nasoseptal” vascularized flap, where normal sinus tissue is moved to cover the surgical defect, has significantly decreased the rate of cerebrospinal fluid leakage (CSF leaks) after surgery. Post-operative CSF leaks, if untreated, can result in meningitis, which can be fatal. Over the last seven years, we have not had a CSF leak for chordoma surgery.

If complete tumor removal is achieved by surgery, no further therapy is needed unless there is future tumor regrowth. However, in the instance of a residual tumor i.e. tumor that was unsafe to remove, additional treatment may be necessary, especially if there are signs of growth. The best treatment options include stereotactic radiosurgery or proton beam radiation, or a combination of the two. These options are performed in conjunction with our radiation oncology colleagues. The radiosurgeon plays the important role of identifying the recurrent tumor to be targeted and protecting at-risk structures when possible. Both stereotactic radiosurgery and proton beam radiation have adequate tumor control of about 80 percent, with a slight advantage to proton beam depending on the tumor location.

If complete tumor removal is achieved by surgery, no further therapy is needed unless there is future tumor regrowth. However, in the instance of a residual tumor i.e. tumor that was unsafe to remove, additional treatment may be necessary, especially if there are signs of growth. The best treatment options include stereotactic radiosurgery or proton beam radiation, or a combination of the two. These options are performed in conjunction with our radiation oncology colleagues. The radiosurgeon plays the important role of identifying the recurrent tumor to be targeted and protecting at-risk structures when possible. Both stereotactic radiosurgery and proton beam radiation have adequate tumor control of about 80 percent, with a slight advantage to proton beam depending on the tumor location.

To date, no medication has been found to be the “magic bullet” to treat chordomas. However, there are a few promising options, especially when genetic targets are identified. Naturally, our patients’ chordomas are evaluated with thorough genetic sequencing to analyze gene mutations. If the patient is a candidate for targeted therapy, this can be an option for our neuro-oncologists. At the Saint John’s Cancer Institute, we have a number of studies for chordoma where we are analyzing potential treatment options for chordoma patients.

Conclusion

Chordomas can present with subtle symptoms and have an insidious growth rate. Treatment options are tumor biopsy followed by minimally invasive tumor resection. Some patients may require radiation therapy if there is tumor growth following surgery. Leading-edge research has identified several potential medications that may offer some benefit for patients with recurrent chordomas. We at PNI and the Saint John’s Cancer Institute are able to offer a comprehensive approach to chordoma patients with our team of neurosurgeons, ENT surgeons, ophthalmologists, endocrinologists, radiation oncologists and neuro-oncologists.

For more information or for a consultation with one of our experts, contact us at 310-582-7450.

Garni Barkhoudarian, MD, is a neurosurgeon with a focus on skull base and minimally invasive endoscopic surgery. He has particular interest and expertise in pituitary and parasellar tumors, brain tumors, skull-base tumors, intra-ventricular brain tumors, colloid cysts, trigeminal neuralgia and other vascular compression syndromes. He is an investigator in a number of clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of various medical or chemotherapies for pituitary tumors and malignant brain tumors. For virtually all tumors and intracranial procedures, Dr. Barkhoudarian applies the keyhole concept of minimizing collateral damage to the brain and its supporting structures using advanced neuroimaging and neuro-navigation techniques along with endoscopy to improve targeting and lesion visualization.

About the Author

Mahyar Pakizegee

Mahyar Pakizegee is a fourth year baccalaureate student at the University of California, Los Angeles majoring in History. His goal is to attend medical school and pursue his dream of being an inspiring physician. He is a contributing author under the guidance of Dr. Garni Barkhoudarian, neurosurgeon at Pacific Neuroscience Institute.

Last updated: August 4th, 2020