Charles’ Story: Parkinson’s Disease and Deep Brain Stimulation

by Guest Author

Charles was living a full life when Parkinson’s disease hit. Although a progressive neurodegenerative disease affecting movement, there are medical and surgical treatments available to help with symptom management. Read this moving and heartwarming account of the impact of DBS surgery on Charles’ life.

A GRATEFUL PATIENT’S EXPERIENCE WITH PARKINSON’S AND DBS: THE FULL STORY

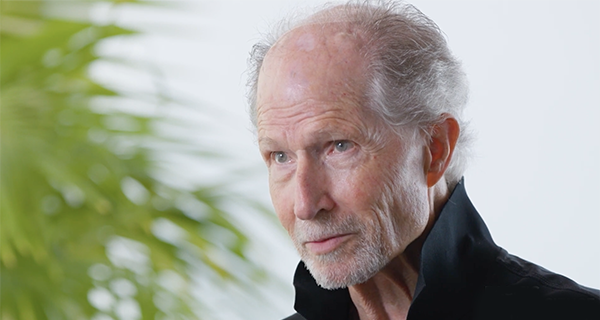

I am seventy-seven years old, happily married for a couple of decades, and retired after more than 30 years from a practice in applied philosophy (psychology). During our first 15 years together, Mary and I enjoyed traveling for 3 to 4 months a year. Before we met we each had a history of adventure travel (Borneo, Madagascar, Nepal, Tibet, Japan, Indonesia, etc). We continued traveling together to Africa, many countries in eastern and western Europe, Iceland, the UK, the Amazon and elsewhere in Peru, Bolivia, and across the United States. We enjoy many styles of music, both of us learned to paint in our retirement, are very active at the gym, and have enjoyed hiking, playing racquet ball, ping pong, surfing, and having dinner parties. My wife was also a psychologist. We met at Esalen Institute in Big Sur during a week long Tibetan meditation workshop.

PART 1: THE PROCESS OF DIAGNOSIS

More than a decade ago, I began to experience many small, strange symptoms. My sense of smell diminished, then I lost it entirely. I would occasionally veer off to the left when walking. My handwriting became smaller and smaller and more illegible. I began to have problems with my skin for the first time. My voice softened then disappeared for two weeks. I often felt dizzy. My posture worsened. I had small tremor in my left hand. I felt somewhat slower physically and had daytime fatigue. In tiny increments, my ability to sleep easily and deeply was increasingly disturbed. Muscles began to tighten and cramp. I noticed that I was losing my edge in all things. I was no longer a highly skilled driver. I could no longer get maximum scores on “Whack-a-Mole” on the Santa Monica pier. Stress of any type became more difficult to manage. My weight, which had been stable for fifty years began to drop. I no longer had the boundless energy that I had always had. I became hesitant while hiking and fearful on stairs. I was besieged by morning nausea that kept me in bed until mid afternoon. I felt shaky and weak, with muscle pain, fatigue, and feelings of incredible vulnerability.

For a long time I tried to dismiss some of these symptoms as simple aging. But, something was clearly wrong. My body knew it and was sending out distress signals. The diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease, which neither I nor any of my doctors suspected, is difficult to make because of the many forms that the condition can take.

I was referred to one specialist after another: dermatology, urology, allergy, immunology, neurology, otolaryngology, and sleep neurology. Diagnostic tests were ordered. At one point, nineteen vials of blood were drawn and sent off to the lab and MRIs were ordered of my spine and brain. It was feared that I might have a brain tumor. All the results came back negative. My primary care physician hypothesized that i was “depressed and anxious”, and would not get better until I accepted those diagnoses and treated them. I had spent thirty years diagnosing and treating clients who suffered depression and anxiety. Clearly it was not “all in my head”. Although I had a right to feel depressed and anxious, I was not. One would think that with all these physicians and tests, a diagnosis of Parkinson’s would have been made long before it was. I persisted until my neurologist at the time felt that mild cogwheel rigidity was probably indicating Parkinson’s. This disease manifests so differently for each person that few fit the standard diagnostic profile. My problems were mostly not the typical signs and symptoms that are used to diagnose, except for limited arm swing when walking. Taking that into consideration now makes it understandable that the diagnosis was especially hard to make in my case. To this day, dysautonomia (which is a dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system) is my most troubling condition because it affects every function of the body, conscious and unconscious, such as blood pressure, temperature regulation, pupil dilation, breathing and the beating of the heart. Each person is assigned their own unique constellation of symptoms.

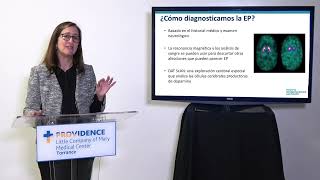

PART 2: THE DIAGNOSIS. WHAT IS PARKINSON’S DISEASE?

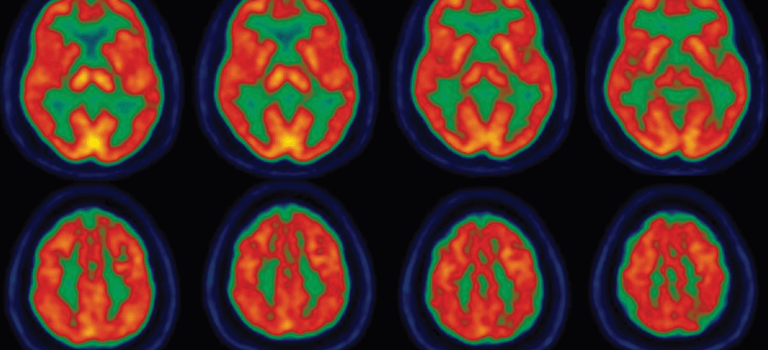

Parkinson’s disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder, meaning that brain cells die in a part of the brain that produces the neurotransmitter dopamine which is required to communicate with other neurons (nerve cells) in the body and in the brain. It has been estimated that by the time one gets the diagnosis, one has lost 75 to 80 percent of these cells. It’s like having an eight cylinder auto that is firing on two. It remains undetectable for a period of time, because of the human ability to compensate for the loss.

Parkinson’s is sometimes referred to as a dopamine deprivation disorder, also known as the shaking palsy, but it is so much more. It affects everything: brain, mind, body, mood, memory, and cognitive function. Parkinson’s is a formidable opponent. Even Mohammad Ali, perhaps the world’s greatest fighter, was unable to triumph over it. One of the most common reactions to such a diagnosis is denial, which serves the disease very well; because its opponent, you, is in the ring both deaf and blind.

I know that I will eventually lose the war, but I continue to win most battles as measured by my physical therapists and trainers. This happens when one creates new neural pathways.

PART 3: TREATMENT OF PARKINSON’S

When I was finally diagnosed with Parkinson’s, I joined a gym and went 226 times in the first year. I am fortunate that my better two-thirds (my wife Mary, of course) enjoys working out. My “gym”, Beach Cities Health Club, is the only medically certified fitness facility in California. There, I have worked with trainers, yoga and pilates instructors, and my own fitness routine. I began physical therapy with Re+Active Physical Therapy and Wellness, a group of doctoral level PT’s and Occupational Therapists who specialize in movement disorders. I asked for Re+Active’s recommendation of a movement disorders neurologist who “thinks outside of the box”, and they referred me to Dr. Melita Petrossian of Pacific Neuroscience Institute.

In my first meeting with Dr. Petrossian at the Pacific Movement Disorders Center, I knew that I had arrived at a special place with a special physician who truly understood. She immediately became the captain of my team, along with her Nurse Practitioner, Giselle Tamula.

Parkinson’s cause is unknown and there is no cure. It is unstoppable, but certain exercises can slow the progression. And there are Parkinson’s disease drugs which can help by introducing dopamine into the brain and other drugs which can help by keeping available dopamine in the brain. The gold standard treatment is Sinemet (carbidopa levodopa), which conveys dopamine to the brain. It worked well for me for a while, then made everything intolerably worse by augmenting my severe Restless Leg Syndrome, an unrelated neurological disorder. I had to be on my feet and moving almost 24 hours per day, which was unbearable. I next tried a dopamine agonist, Rotigitine (Neupro 24 hour patch), in a dose which also augmented RLS (increased symptoms), I had to limit the dose of Neupro, so that it was ineffectual for Parkinson’s symptoms. Without the full effect of these drugs, life is a greater challenge. It is as if your only computer, your brain has a computer virus that is spreading, and randomly attacking and increasingly affecting every function. It is a private horror show.

Unable to take these medications, I was a mess. I had feelings of anxiety, feeling super vulnerable, my movement became slower (bradykinesia), tremor became more of a problem, I was unable to eat soup with a spoon, I was afraid of stairs, fearful of getting trapped in small spaces, dragging and scuffing my feet, easily frustrated, simple things made me grouchy.

Exercise is medicine for Parkinson’s, but it was difficult to exercise intensely because of my physical and mental state, with no medication to help control these symptoms. Vigorous exercise is the only treatment option that has been scientifically proven to slow the progression of the disease, so it was especially important to seek another treatment option.

PART 4: DEEP BRAIN STIMULATION (DBS) FOR PARKINSON’S

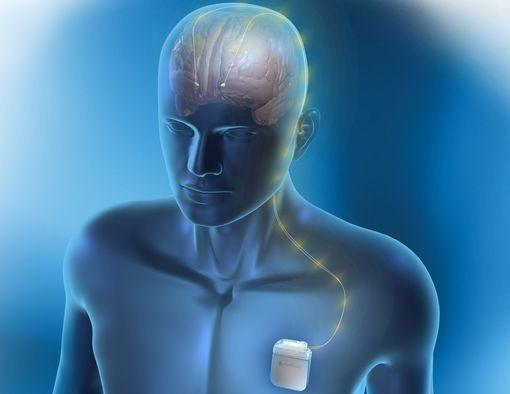

During DBS surgery, the surgeon places electrical leads in the brain which send electrical pulses to a small part of the brain to help control some symptoms. These electric pulses smooth out the erratic neural electrical activity of Parkinson’s. While transformative for some, DBS is not for everyone.

Dr. Petrossian began talking to me about DBS a year before I had the procedure because I was approaching a window of opportunity for maximum positive results, and she wanted Mary and I to contemplate and get used to the idea. Usually I am freaked about surgery, but because Dr. Petrossian was suggesting it, I was all for it. A meeting with a neurosurgeon, Dr. JP Langevin, was scheduled. I was impressed by his manner, which was unusual for a surgeon, humble, gentle, sweet, lovely, and obviously competent. There was a battery of psychological tests to be taken to see if I qualified. I was thrilled to have passed the tests with flying colors. I could hardly wait and went in to the procedures more than thrilled and very relaxed. Dr. Langevin explained in detail why he and Dr. Petrossian had selected a Boston Scientific device, with a battery that one can recharge with a device placed on top of the skin. I have met many people with DBS devices that were not as fortunate as I was in their choice of device.

When I had the device installed, before it was activated, I felt immediately better. This is not uncommon and fades over time. As soon as it was activated, I was extremely energetic and proclaiming “I AM BACK” while gesturing like those tall tube puppets in front of car dealers or tire stores. A temporary personality change or exaggeration of an existing trait is a common result of mild brain inflammation and swelling from the surgery, along with adjustments that need to be made in the stimulation itself, as the best sites in the brain are found (others might have a very different reaction.) Mania is fun for the manic person and a delight for some others… for a while. In the office I felt so good that I feared if they could see how I felt, then they would take it away. It was a difficult period for Mary because I was apparently hard to communicate with, and insensitive to her position. As the mania calmed down, I felt truly good and Mary and I were eventually able to communicate effectively again.

I felt as if everything I had lost was now once again returned to me. The programming was adjusted numbers of times over a 6 month initial period, during which my emotional presence got slowly better. I once again became more kind, helpful, gentle, and responsive, able to share and respond to feelings.

Post DBS, I immediately felt good and stable enough again to exercise vigorously. Since I can take none of the usual PD drugs, exercise is the predominant way I can generate dopamine which helps with movement, agility, strength, tremor, balance, depression, anxiety, digestion, sleep, energy, thinking, and memory. Exercise is medicine because it generates dopamine and other neurotransmitters in the brain, which enhance wellbeing, happiness and better health. As part of filming for my story for PNI, Giselle turned off the DBS. My symptoms were very mild, slightly increased tremor and slight difficulty with turns when I walked. I attribute my slow progression of the disease to DBS, exercise and physical therapy. Physical therapy is also brain training. I know several people who were diagnosed with PD at the same time I was, with roughly the same symptom severity, who did not have Pacific Neuroscience Institute, nor DBS, and have progressed significantly.

PART 5: GRATITUDE

I consider myself to be lucky, even with Parkinson’s initially, and now even because of it. I was skeptical when others talked about being grateful to have their disease. Even as I realize that everything will become more challenging, I intend to get better at being grateful for what I still have without giving much energy to what I have lost. Parkinson’s is not who I am, it is merely what I have through no fault of my own. I have Parkinson’s but Parkinson’s does not have me. Having Parkinson’s has helped me to further develop acceptance, resilience, perseverance, and gratitude for everything and everyone in my life. Simply knowing that I won’t always be able to do all the things I enjoy, I strive to enjoy everything I do with ever-increasing appreciation and gratitude.

PNI, Dr. Petrossian, Dr. Langevin, Boston Scientific and its representatives, and all of the technical miracles which made DBS possible, deserve a heartfelt thank you.

Meet the Pacific Movement Disorders Team

Useful Links

- Medicines for motor symptoms management of Parkinson’s disease – pdf 1-sheet download

- Non-motor symptom management of Parkinson’s disease – pdf 1-sheet download

- Pacific Movement Disorders Center

- Deep Brain Stimulation for Parkinson’s disease

Videos related to Parkinson’s disease and DBS

Related Articles

Last updated: August 9th, 2023