A Smile Returns After Facial Paralysis

by Guest Author

Dr. Amit Kochhar performs an advanced type of facial nerve surgery that restores movement and function in patients with facial paralysis.

Imagine you can no longer smile. What would that do to your ability to communicate or even experience emotions? This is the reality for those with facial paralysis.

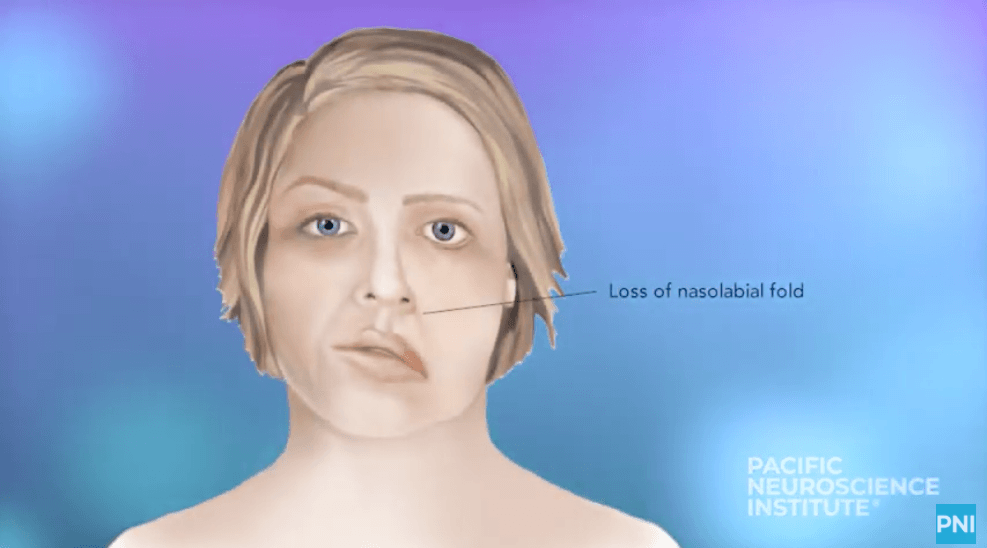

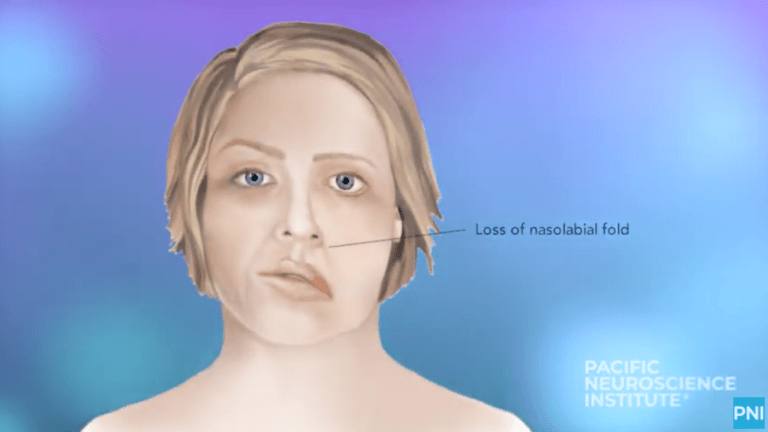

There are a wide variety of reasons people find themselves with the condition, including Bell’s palsy, Ramsay Hunt syndrome, trauma or tumors such as vestibular schwannoma or parotid cancer. Known as facial palsy, the paralysis usually affects only one side of the face.

Amit Kochhar, MD, Director of the Facial Nerve Disorders Program at Pacific Neuroscience Institute® (PNI®), is one of a small number of surgeons who perform dynamic facial reanimation, a surgery that may involve re-routing nerves and muscles of the head and neck.

In the most severe cases, Dr. Kochhar transplants a muscle from the leg into the face to restore facial movement. Known as a gracilis free tissue transfer, it’s one of the most complex procedures a surgeon can perform. “In the whole state of California, there are maybe 10 doctors who do it,” says Dr. Kochhar, who is double board-certified in otolaryngology, head and neck surgery as well as facial plastic and reconstructive surgery.

Urgent situation

For the facial nerve, this is the equivalent of having a heart attack.

Dr. Amit Kochhar

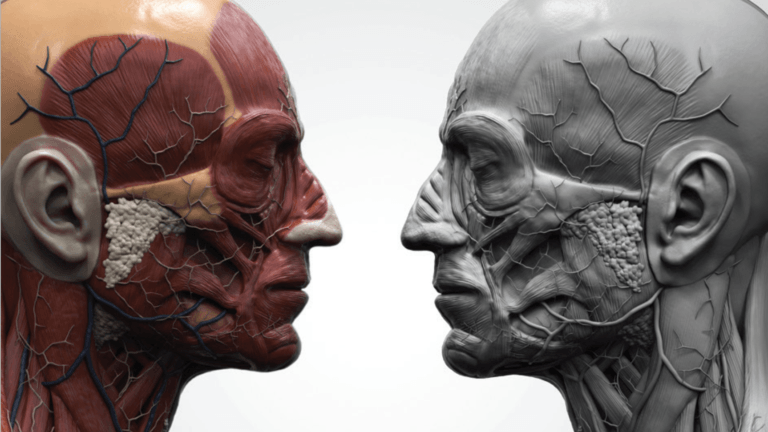

Dr. Kochhar emphasizes the importance of seeing a physician immediately if you have symptoms of facial palsy. “For the facial nerve, this is the equivalent of having a heart attack,” he says. The first step is to determine the cause of the paralysis. This may involve diagnostic imaging such as an MRI, but, says Dr. Kochhar, “it’s really the physical examination that’s critical” in reaching a diagnosis and treatment plan.

Once the cause of the facial paralysis is determined, it may mean surgery to remove a tumor that’s damaging the facial nerve. Often this involves a team approach to treatment. Dr. Kochhar says he is very fortunate to work with an incredible group of specialists at PNI: “Patients are able to one-stop shop and have all their needs met by experts in the field.”

“When a patient visits me, they’re usually thinking only about their face’s appearance,” says Dr. Kochhar. “However, one of the most important things to address with facial paralysis is the eye not closing properly. That makes patients more susceptible to infection and even blindness.” Dr. Kochhar works closely with his ophthalmology colleagues at PNI who perform eyelid reconstruction to help the patient be able to close the eye completely.

For patients who have suffered hearing loss caused by the same tumor that damaged their facial nerve, Dr. Kochhar works with neurotologist Courtney Voelker, MD, PhD, who fits patients with cochlear implants to restore hearing after the removal of vestibular schwannoma (aka accoustic neuroma) tumors.

Dr. Kochhar also notes that patients may not be able to speak clearly or eat normally because of loss of muscle control in the mouth and tongue. PNI has two speech and language pathologists who work with patients with facial paralysis to overcome those limitations.

Microsurgery mastery

Dynamic facial reanimation surgery takes four to six hours and involves of medical team of seven people. Dr. Kochhar and his assistant begin by mapping out the nerves in the face and evaluating which one will be the strongest donor nerve. He then harvests tissue from the patient’s inner thigh, including its blood vessels. Using a special microscope, he attaches nerves and blood vessels of the gracilis muscle to ones in the face to replace the patient’s inactive smile muscles. This work requires Dr. Kochhar to use his expert judgment to place the muscle so the movement of the new “smile” matches the other side.

The results take several months to be apparent because movement only returns as the nerves heal. “Patients won’t get movement until about four to six months after surgery and they have to learn how to smile again,” says Dr. Kochhar. To activate the new muscle, patients must activate the masseter (chewing muscle) nerve that was re-routed to supply the gracilis muscle. While it’s awkward at first to clench their teeth and make a smile, most patients say it becomes second nature over time.

Restored quality of life

Dr. Kochhar says his highest priority is to improve his patients’ quality of life, particularly because it’s common for patients with facial paralysis to suffer from anxiety and depression. When his patients return to see him excited to share their new smile, he knows he has made a difference.

“While I can’t return their old smile exactly as it was,” says Dr. Kochhar, “I do my best to give every patient a new one that will help make them whole again.” Together with the team at PNI, Dr. Kochhar is giving patients their quality of life back, one smile at a time.

About Dr. Amit Kochhar

Dr. Amit Kochhar, MD, is double board-certified in Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery and Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. He is the director of the Facial Nerve Disorders Program at Pacific Eye, Ear & Skull Base Center, Pacific Neuroscience Institute, Providence Saint John’s Health Center in Santa Monica.

Adapted from original article in Health Matters from Providence Saint John’s Spring 2024 issue.

Related Articles

Related Videos

A PNI Minute: Gracilis Free Tissue Transfer for Facial Paralysis | Dr. Amit Kochhar

A PNI Minute: Gracilis Free Tissue Transfer for Facial Paralysis | Dr. Amit Kochhar

A PNI Minute | What is Bell’s Palsy?

Dr. Amit Kochhar talks about symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment of Bell’s Palsy. Bell’s palsy is a paralysis or weakness of the muscles on one side of your face. Fortunately, the…

A PNI Minute | What is Bell’s Palsy?

Dr. Amit Kochhar talks about symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment of Bell’s Palsy. Bell’s palsy is a paralysis or weakness of the muscles on one side of your face. Fortunately, the…

Synkinesis after Bell’s Palsy | Nicky’s Grateful Patient Story

Five days after the birth of her second son, Nicky developed Bell’s palsy, a facial paralysis affecting one side of the face. In a majority of people symptoms resolve with…

Synkinesis after Bell’s Palsy | Nicky’s Grateful Patient Story

Five days after the birth of her second son, Nicky developed Bell’s palsy, a facial paralysis affecting one side of the face. In a majority of people symptoms resolve with…

A PNI Minute | Treatments for Facial Paralysis

Dr. Amit Kochhar talks about the treatment of Facial Paralysis. Facial paralysis is devastating to one’s identity. Patients with facial paralysis experience physical, social, and emotional changes. At PNI, our…

A PNI Minute | Treatments for Facial Paralysis

Dr. Amit Kochhar talks about the treatment of Facial Paralysis. Facial paralysis is devastating to one’s identity. Patients with facial paralysis experience physical, social, and emotional changes. At PNI, our…

A PNI Minute: Gracilis Free Tissue Transfer for Facial Paralysis | Dr. Amit Kochhar

A PNI Minute | What is Bell’s Palsy?

Synkinesis after Bell’s Palsy | Nicky’s Grateful Patient Story

A PNI Minute | Treatments for Facial Paralysis

Last updated: May 14th, 2024